Humanity will probably not remain a single species in the future. There’s a thing called the founder effect, which “…occurs when a small group of migrants that is not genetically representative of the ancestral population settles in a new area”.

You can probably already see where this is going.

It looks pretty clear that extensive human settlement in space will lead to powerful founder effects – genetic and cultural.

Colonists will be strongly selected for peak health and high IQ, but also for personality traits like adventurousness, curiosity and optimism.

Those things are heritable. This is especially interesting in light of growing scientific evidence there are powerful, often dominant genetic causes of a vast variety of behavioural and psychological traits – including these ones, and even political leanings.

Certain valuable traits will become dominant in entire new human populations.

Read that sentence again, and then once more.

Who do you expect will choose to go settle space? Brave mavericks driven by a spirit of progress and a thirst for exploration, or the timid, anxious, pessimistic, self-hating deathists who won’t get on a rocket because it looks a bit like a penis?

No, those errors of nature will stay behind, probably protesting that others are choosing life. It is natural selection. Let the regressives stay, and the explorers, pioneers, frontiersmen and voyagers settle the universe. To each his own. The “please just make it all end” misanthropes and entropists can stay behind with mother (Earth), which has always been their basic psychological motivation, while the energetic and vital – the ancestors of future humanity – prepare chariots of fire to the stars.

To illustrate the speed and power of founder effects, consider it has been barely 100 000 years since modern humans strolled out of Africa. The resulting variaton – phenotypic, behavioural, cultural – is profound. All it took was a couple of population bottlenecks during migrations and in Last Glacial Maximum refugia.

Now imagine what might happen over long periods in space – with more varied environments, potential cultural isolation and powerful founder effects.

Looks excellent to me, to be honest.

The founding populations will already be appreciably different – physically a little, and psychologically and behaviourally a lot. Those differences will amplify as they (we, for the love of fuck, let it be we) interbreed and select for such traits ever more strongly.

“When a newly formed colony is small, its founders can strongly affect the population’s genetic makeup far into the future. In humans, which have a slow reproduction rate, the population will remain small for many generations, effectively amplifying the drift effect generation after generation until the population reaches a certain size.“

Across human history, a tale of exploration, settlement, development and ultimate stagnation and entrenchment, leading to a repetition of the cycle has played out.

Here’s how it usually works: a founding population of intrepid spirits (or desperates) risks life, limb and sanity to break new ground, driven as often by curiosity and economic opportunities as by persecution in the ancestral homeland. Typically, there are multiple migration waves driven by different motivations. The mavericks eventually build a successful society that outshines everything they left behind, thanks to:

- The natural wealth of the newly settled space.

- Personal qualities of the settlers, selected above ancestral averages.

- Green-field social organization without legacy systems and entrenched interests. This is so tremendously important. Founders get to build society from first principles. More often than not, they find new ways of doing things which can be generalised and back-propagated to ancestral homes – like American democracy did for Europe – but which could not happen as a reform from within (too much resistance), and had to come from outside. Mars will save Earth like America saved Europe, repeatedly. For a smaller-scale example, consider that huge established companies are trying to emulate the modus operandi of startups.

This is the “new world paradigm” of progress. You can see this is pretty big.

When the population reaches a certain size, there’s more space for different strategies to succeed, including zero-and-negative-sum chicanery. The frontiersman ethic gets supplemented, and eventually replaced, with the usual social predation, petty politics, institutional creep and rent-seeking, and widespread demands from various people for a “fair share” of something they had no hand in building.

(“Guys remember those loons who left a while ago? They pulled it off, let’s move in, partake in their success and fuck it up for them”).

As they gradually fuck the place up by skewing social organisation and institutions towards their interests, another splinter population of the morally principled, the rejected and the opportunistic leaves to build a better world elsewhere. And the grand cycle of civilization repeats.

It’s a fractional distillation of humanity that has been going on for hundreds of thousands of years. Earth politics are pushing us to eye that red dot in the night sky with longing and hope, and the red wastes of Mars are vastly preferable to the red wastes of communism.

Let what’s best in humanity flourish.

Atlas won’t shrug. He’ll leave.

“The variation in gene frequency between the original population and colony may also trigger the two groups to diverge significantly over the course of many generations. As the variance, or genetic distance, increases, the two separated populations may become distinctively different, both genetically and phenotypically, although not only genetic drift, but also natural selection, gene flow and mutation all contribute to this divergence. This potential for relatively rapid changes in the colony’s gene frequency led most scientists to consider the founder effect (and by extension, genetic drift) a significant driving force in the evolution of new species.”

While genetic changes will take generations, cultural differences will manifest immediately. At first, we can expect a regimented, military-style organization due to the colonists’ material constraints. Central command is both necessary and possible on that scale. That will change as life approaches “normal” conditions of relative abundance, increased complexity calling for emergent rather than centralised order, and colonists wanting to lead more varied and free lives, in what was built with justified, necessary, but temporary total organization.

The ISS isn’t a democracy, while a space station with a million people probably will.

Then, once humanity is reasonably settled in space, we can expect an explosion of variety and experimentation.

“What forms will society take in space?”. Many different. It’s going to be fantastic. We can A/B test different stuff, run controlled experiments, and let everyone choose to live in a society that reflects their values and preferences best. Assuming there isn’t an universal one-size-fits-all “correct answer” and “best type of government”, then variation, competition and “customer choice” are the right way to go.

An entrepreneurial civilization, experimenting, pivoting, sticking to what works. Colonies competing for citizens, instead of colluding to make conditions equally miserable everywhere.

Mutual respect and non-interference will be extremely important – there must be no “nuke the infidels” or “overthrow the capitalists” elements. Live and let live, even though the usual caveats apply – i.e. you should probably do something about a genocidal tyrant or crazy murderous cult that organizes terrorist attacks in other people’s peaceful settlements.

There’s a trope in science fiction about ancient progenitor races seeding the universe with life. A good mind-spinner is it might be us. We may be living in the late prehistory of a universe-spanning founder race. This makes everything we do important.

How much will humanity branch out? There’s no limit. A much more interesting question is how quickly – and the answer depends on how fast and how scalable and affordable we can make space travel.

In fact, here’s a law I’m not sure anyone has phrased before, so here goes for the history books: humanity in space will genetically, culturally and politically diverge in direct proportion to slowness of travel.

The time it takes to communicate with or physically travel to a colony determines how intimately it remains tied with the ancestral population. If we figure out faster-than-light travel, humanity will probably remain largely homogenous. If, on the other hand, it takes ages to go anywhere, expect massive divergence. So massive that Homo will re-become a genus, rather than a single species.

In the long run, differences will arise that will make the variety of present day human races look laughable, and the cold war look like a minor doctrinal misunderstanding. If you think we have ethnic and cultural, genetic and memetic differences on Earth, just wait till we’ve been in space for a few hundred generations.

“As a result of the loss of genetic variation, the new population may be distinctively different, both genotypically and phenotypically, from the parent population from which it is derived. In extreme cases, the founder effect is thought to lead to the speciation and subsequent evolution of new species.”

Travel and communication speeds also place an upper bound on political unity – since political power is based on a (however subtle) threat of violence, it is virtually impossible to project power to other stars and prevent self-determination of colonies in the absence of faster than light travel.

If it takes years or decades even to relay a message, political unity is not only impractical, it is impossible.

In such scenarios, the likely result is a patchwork of sovereign units forming no greater whole, and indeed nobody knowing humanity’s total extent, If,on the other hand, we have Star Trek technology, we can have a Star Trek society – a coherent federation with limited planetary cultural self-determination within an overarching political structure.

As for military force, every precaution should be made to avoid war in space – what they don’t tell you on Star Trek is that any starship is a weapon of mass destruction just by virtue of the energy requirements, and in the event of conflict, mutually assured destruction, or at the very least unacceptable damage incurred by all sides, is a certainty. Let the certainty act as a deterrent.

Wars in space will either be nonexistent, ritualised or total.

A good question is why wars in space would even happen – space is full of all kinds of stuff, so fighting over resources sound unlikely – again in proportion to ease and speed of travel. Warping over to the next star is always wiser than risking total annihilation over a bunch of minerals.

Wars over stuff are unlikely unless we find something really special – like a highly colonisable planet (assuming they are rare, which they might not be), or even a life-bearing one (again, assuming they are rare). By the way, we should definitely respect alien life and not genocide the shit out of entire ecosystems, but that’s self-evident.

Few other causes for conflict are plausible. Unfortunately, those include the most dangerous and evil causes of all – wars of religion/ideology/philosophy. They’re the most dangerous, because they discount normal risk/benefit analysis and enable irrational actions.

I mentioned that humanity might lose track of itself. There are, in fact, at least two ways that might happen. One is if space travel and communications are slow. Suppose a colony establishes daughter colonies of which Earth (or any sister colony) is unaware. Iterate a few times. In this scenario, disunity is an effect of space travel being hard.

It can also happen if space travel is easy. If faster-than-light (FTL) travel is widely affordable, there will be so much going on that nobody will be able to keep track of everything, and there may be entire unknown branches of humanity – an exponential explosion of civilization. Make your own conclusions for genetic and culture variation.

There’s a a range of intermediate scenarios where FTL travel is possible, but hard – then it may be easy to keep track of everyone. It would also be a future of big organisations and powerful central governments exclusively in control of interstellar travel technology, rather than the more likely (and desirable) technology-enabled decentralised smorgasbord of variation and choice.

A lot therefore depends on the limits of physics, and on the economies of scale and miniaturisation of future spacecraft technology – whether faster than light propulsion is 1) even possible and 2) intrinsically hard, or economical as consumer technology akin to cars.

By the way, since we haven’t met any aliens yet, that implies space travel is either hard, or intelligent life is rare. Or we’re being prime directived.

It is possible that space travel is an irreducibly hard technical problem that will never be commoditised – but keep in mind that people, including Very Smart People, thought the same thing about the device you’re reading this on, and a lot of other stuff you use routinely.

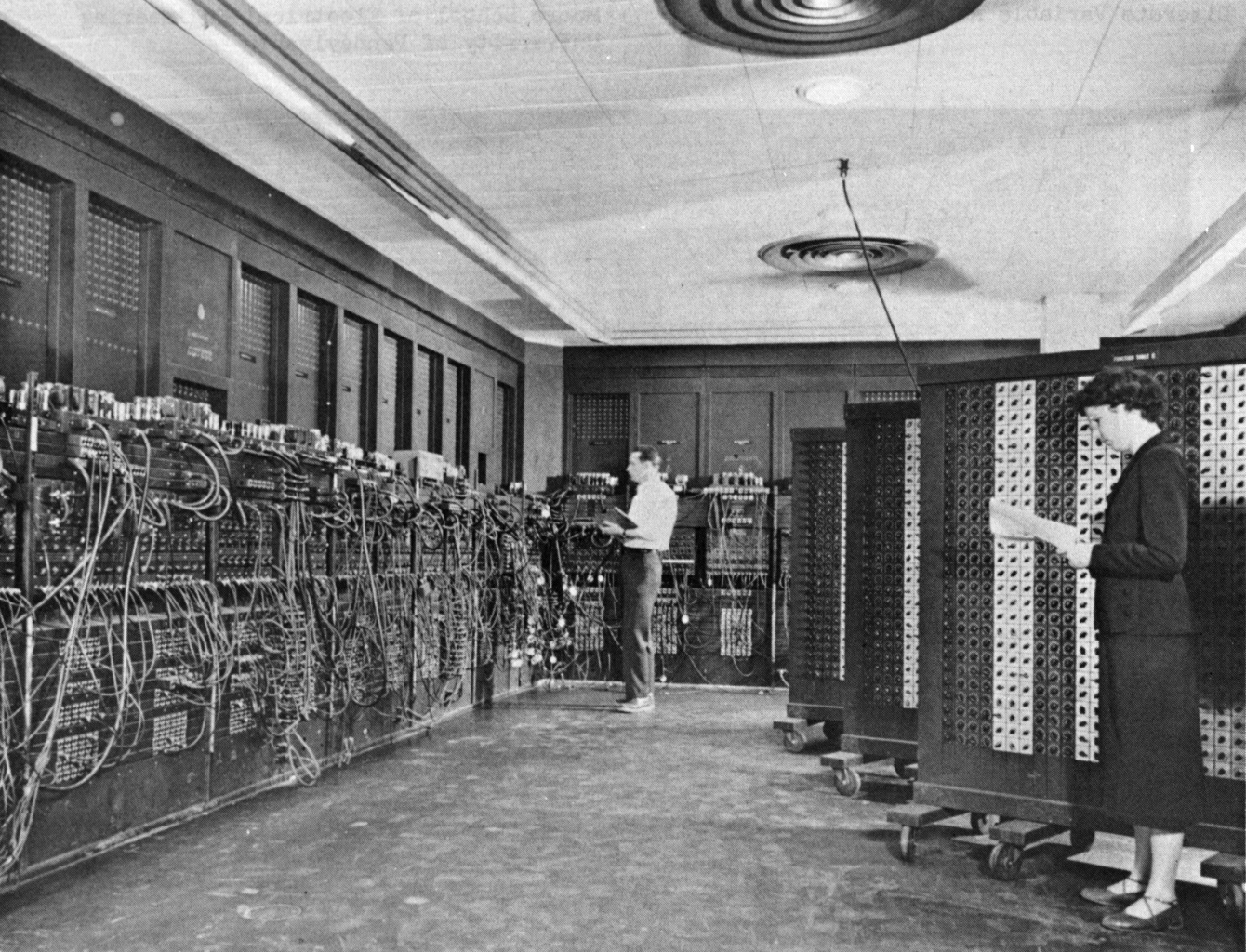

“Computers will never be small or cheap, and why would anyone ever want a personal one” they said.

This is what humans do – we take miracles of technology that were once impossible moonshot projects occupying legions of scientists, triumphs of the human spirit costing billions to even approximate, and within a generation of the first clunky prototype, turn them into consumer products that teenagers use to send each other pictures of their genitals. We turn the miraculous into the commonplace in the best way.

Which is why I believe it will take a couple of decades at most from a prototype warp drive that costs half a trillion dollars to a mass produced consumer model that yobbish louts crash into scenery and decorate with far too many lights. The Ford T effect.

There are probably hard limits on possible technology, but they’re much farther out than moving bits of metal around fast. Including using loopholes in physics.

It always feels like we’re pushing the limits of technology. It’s a form of hindsight bias, because things that already exist are easy to imagine, while those that don’t are hard. But on an objective scale, we’re barely getting started.

If all possible technology is on a scale of 1 to 100, we aren’t in the nineties or even in double digits. We’re certainly not far above 2.

Humanity will colonise space in any scenario where we haven’t gone extinct, or insane. Whether slowly or quickly, that’s still to be seen.

One more thing. This might be the kind of wide-eyed optimism that looks ridiculous in retrospect, and I’ll be happy to retract it in three hundred years, but I believe going to space will have a profound moral effect.

It’s impossible to look at the Earth from space without a moral epiphany. If the main cause of evil is lack of perspective, this perspective is as good as they get.

Just look at it.

The experience is a powerful antidote to the pettiness and amygdala-driven monkeybrain games that plague Earth. The cruel, mad, vicious ape melts away when faced with the splendor of the universe.

We won’t become saints by venturing beyond Earth orbit (going to the heavens?), but it might just make us nicer enough to make the future less murdery and more enlightened than the past.

Going to space is THE most important thing to care about right now. Nothing else comes close. It’s the next “life crawling out of the ocean” magnitude leap. I am thrilled we are finally serious about doing it.

Mars is only the beginning.

Humanity will diverge in direct proportion to how hard it is to get around in space.

For added fun, add gene editing, nanotechnology and cybernetics.

100 000 years from now, humanity will not be phenotypically coherent a single species.

Oh the numerous porn genres awaiting.

Enjoying the reading? Buy me a ticket to Mars.