By now, I could start most articles with “popular opinion has stuff the wrong way around“.

For instance, you hear people saying they want to start a business, but worry that “the economy” might not be good enough right now.

Let me ask you a question, and this one is really easy when you think about it: What do you think comes first, people doing useful stuff, or a good economy?

What the sentiment amounts to is “It’s necessary to sit idly about, until the augurs in central banks declare economic conditions auspicious.”

Which is equivalent to: “We mustn’t work, GDP and employment aren’t good enough!”

= “We mustn’t work, the economy isn’t good enough”

= “We mustn’t improve the economy until it gets better”.

Well it sure as hell won’t get better until more people do more useful stuff.

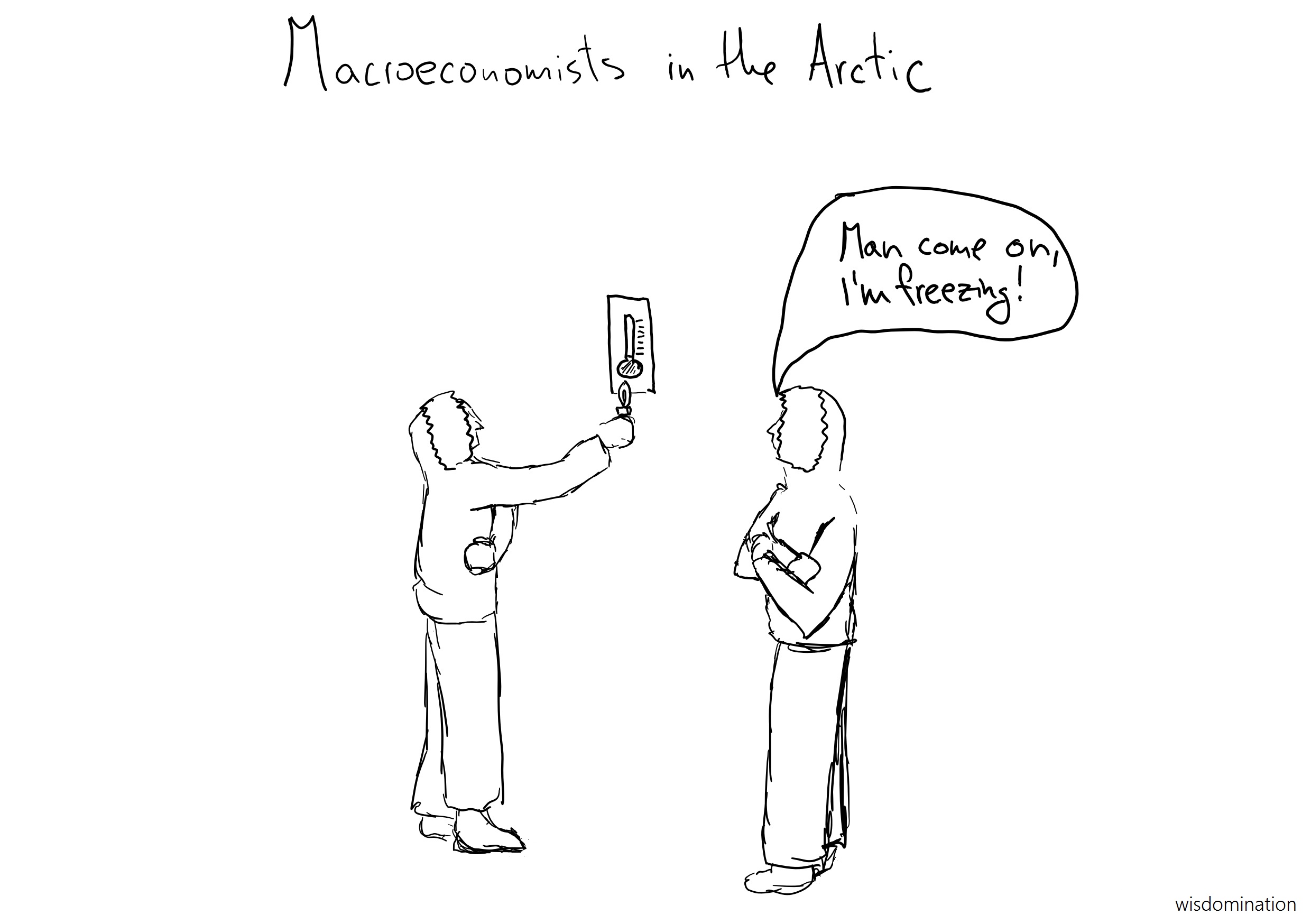

“We shouldn’t start a fire, it’s too cold.”

Direction of causation matters. Sentiment follows facts, not the other way around. Remember the discipline and motivation thing.

Yeah yeah, the sentiment and business climate and squiggly lines in the markets influence how the winds blow in your sails, but:

- If you’re doing important work and doing it well, “the state of the economy” is almost irrelevant. They will come.

- “The state of the economy” is only an aggregate of what people are doing. Being dissuaded from doing something by “the state of the economy” is a nasty feedback loop.

- If your business helps people create value, or to save money, a “bad economy” is actually the best time to start.

There is no such thing as a bad economy if you have a good enough plan.

A less kind way of saying that would be that if a business depends so completely on external conditions that you can’t do it unless they’re excellent, it is probably not worth doing to begin with. If your businessplan is to tailride on sentiment or some movement of collective irrationality, you might make money, but you’ll never build anything important.

Who cares about the wind in your sails when you’ve got an engine. Good business creates sentiment, not the other way around.

The economic crises now are largely crises of demand. Which just means everybody already has everything they want and can afford, and there’s nothing good and affordable left on offer. So offer people something good and affordable. Reacting to a qualitative crisis of demand by refusing to provide higher quality supply is just dumb.

A great business creates it’s own market, and external conditions (short of war or bad legislation) are almost irrelevant. Nobody ten years ago knew they needed a tablet. Was there a boom in the tech sector that caused the tablets? Or did the tablets cause the boom in the tech sector? It’s a tough one.

I am excited about the startup culture for the excellent reason that it successfully weds human nature (i.e. greed) to progress. You win by doing something radically new, striking new grounds, pushing the frontiers, and, soppy as it might sound, benefitting humanity. (There’s only one lasting source of prosperity – technology. Cell phones and fintech did more for developing world economies than decades of development aid that mostly just entrenched dictators and enriched various Geneva-based “aid” agencies). It’s this kind of entrepreneurship that macroeconomic models simply have no power over, and can at best later account for and describe.

Granted, the odds of any one company changing the general economic mood or creating a new market are low. But that needn’t be the goal. What if a hundred people start moderately successful startups? Or a thousand? What if the long tail suddenly gets serviced? Remember, it’s bigger than the fat bit of the curve.

Even if you don’t significantly impact country (or world) wide statistics, that probably wasn’t your goal. Your goal might just be to start a successful company – and whom you recruit and what you do is far more important for that than your country’s trade balance with Singapore or some such fourteenth-level derivate of the realities you’re personally contributing to shaping.

“The economy” isn’t substantially the aggregate statistics, interbank rates and price of copper in Shanghai. Those things matter, but they are products, not the substance of what the actual economy is like. It is nothing more than the aggregate of what people do. So do something.

The economy is you. Grabbing a coffee, fixing your neighbor’s car, going to work and buying a pair of pants. Everything you do is a factor in the grand scheme of things. Sure, it might not be the biggest, but it is real, and the “grand scheme of things” is nothing more than the aggregate of a large number of exactly such everyday interactions.

The abstract, cargo-cult prone top-heaviness of our economic models is a huge issue. There’s a risk of mistaking the map for the territory, and a lot of “let’s fiddle with the numbers and hope it causes the things that would normally cause these changes to the numbers, except we did it artificially” magical thinking.

Abstractions follow from facts, not the other way around.

In the words of W.B. Yeats: “Do not wait till the iron is hot, but make it hot by striking.”

If you wait for favorable conditions, you will probably never start. There will always be enough economic hand-wringing in the news to justify procrastination. I don’t think I’ve ever seen economic news being, one the whole, positive, including during what was later retrospectively branded “the good times.”

In the present tense, nearly all economic news is gloomy. But reality seems to be steadily improving.

If you listened to the news, it would seem the only possible conclusion is pessimism. But when you look at reality, the only possibility is optimism. Trust your eyes before other people’s mouths. The combination of a negativity bias towards the present with nostalgia towards the past yields exactly the opposite image of what’s actually happening.

Humans are notoriously bad at properly weighing good and bad, overemphasizing the latter and discounting the former in all sorts of contexts. It’s why prosperous westerners manage to complain about inequality from their MacBooks while sipping coffee that costs several days’ wages on most of the planet.

When people succumb to such macro fatalism, it can and does easily lead to a tautological situation where the economy is bad, because the economy is bad. But both economic optimism and pessimism are self-perpetuating feedback loops. The key, of course, is to make things better by doing.

When a pessimistic “subduing of animal spirits” happens, it is mostly the too-young-to-know-any-better who start these game-changing businesses, because “they didn’t know it couldn’t be done so they did it”. In other words, it could totally be done, but other people were being irrationally negative.

“Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world, are the ones who do.”

As Y-combinator’s Paul Graham said:

“The economic situation is apparently so grim that some experts fear we may be in for a stretch as bad as the mid seventies.

When Microsoft and Apple were founded.”

Addendum: Waiting for the right arrangement of abstractions to start doing stuff is bad. Expecting them to actively fix the situation is worse:

“The world is sleepwalking into a fresh crisis as investors start to lose faith in policymakers’ ability to revive the global economy, according to the International Monetary Fund”. (source)

I’m sorry, but with that framing, another crisis is not only inevitable, but necessary.

Policymakers can’t revive shit. They can create favorable conditions for people to do it. Important difference.

People waiting for policymakers to fix stuff (and the macro conditions to improve) before starting to do stuff = an implicit command economy.

The best thing for the economy would be for people to start completely ignoring the “rarefied heights” of central banking and monetary policy and start fucking doing stuff.

Reading released pleasant squirts of dopamine in your brain? Return the favour.